THE COLLABORATION OF CLAUDE MONET AND GEORGES CLEMENCEAU: Creating the Grand Decorations of Water Lilies for the Orangerie

Introduction: The Artistic and Political Landscape of Early 20th Century France

In dawn of the 20th century in France was marked by a vibrant and transformative artistic landscape, with the Impressionist movement having laid a fertile ground for the emergence of diverse modern art expressions.1 At the heart of this era stood Claude Monet, a foundational figure of Impressionism, celebrated for his profound ability to capture the subtle nuances of light and his dedication to exploring singular subjects through extensive series of paintings.3 Among his most iconic works are those depicting water lilies, a subject with which his name became intrinsically linked in the public consciousness.3

Monet painting the late Waterlily paintings for his Grand Decorations.

Parallel to this artistic dynamism was the significant presence of Georges Clemenceau, a prominent French statesman who served as Prime Minister during the critical years of World War I, navigating France through one of its most challenging periods.6 It was within this confluence of artistic vision and political leadership that the Musée de l'Orangerie, originally a practical structure built in 1852 to shelter the citrus trees of the Tuileries Garden during winter, would evolve into the permanent sanctuary for Monet's monumental Water Lilies decorations.8

Clemenceau and Monet on the Japanese Bridge in his garden at Giverny.

This transformation stands as a powerful testament to the intersection of art, politics, and the evolving identity of a nation. The Water Lilies at the Orangerie represent not only the zenith of Monet's artistic endeavors but also a profound cultural monument in France, designed to offer an enduring space for peace and contemplation.5 The initial observation here is the remarkable convergence of an artist and a politician, figures from seemingly disparate realms, uniting to create a project of profound national significance. This collaboration underscores a broader trend of cultural spaces adapting to new purposes, in this case, from a functional building to a revered artistic institution. Ultimately, this endeavor highlights how art can become deeply interwoven with the historical fabric and collective memory of a nation.

The building of the Orangerie museum was a greenhouse. In 1852, Napoleon III built it to protect the orange trees from winter snow. Since the purpose of making it was to protect the trees, it was built on the garden terrace along the Seine River. The name of the building was “waterfront terrace.” [https://getparistours.com/orangerie-museum-history/]

Monet's deep engagement with the motif of water lilies began in the late 1890s, a direct result of the meticulously crafted water garden at his estate in Giverny.13 This artistic haven was established in 1892 with the purchase of a marshy piece of land adjacent to his property.3 His intention was twofold: to create a space that pleased the eye and to cultivate a source of inspiration for his paintings.3

Japanese Bridge

Following the installation of a Japanese-style footbridge in 1893, Monet began to introduce water lilies to the pond.14 His dedication to horticulture mirrored his artistic passion 3, as evidenced by his employment of gardeners to maintain the carefully orchestrated landscape that served as his muse.18 Over the years, Monet relentlessly painted the surface of his water lily pond, each canvas a study in the ever-shifting interplay of light and atmosphere across different times of day and the changing seasons.3

To capture the ephemeral qualities of light, he often worked on multiple canvases simultaneously, moving from one to another as the light transformed.6 The ambition to translate these intimate studies into a grand decorative cycle, one that would envelop the viewer in a continuous panorama of water lilies, took root in Monet's mind as early as the late 1890s.3 He envisioned a space where the walls of a circular room would dissolve into a horizon of water dotted with these iconic plants, creating an encompassing illusion of boundlessness.5

Monet's profound personal connection to his Giverny garden is evident, as he himself considered it his "finest masterpiece".18 This period marks a significant shift in his artistic focus, moving away from traditional landscape compositions towards a more abstract exploration of the water's surface.14 The creation of the garden directly instigated the extensive body of water lily paintings, culminating in the ambitious "Grande Décoration." This ambition reflects a desire to transcend the conventional framed painting, offering viewers a fully immersive and contemplative artistic experience.

The Collaboration of Monet and Clemenceau

The realization of the monumental "Grande Décoration" project was significantly influenced by the deep and enduring friendship between Claude Monet and Georges Clemenceau.3 Their relationship, which began in the 1860s and deepened in the 1890s, was characterized by mutual admiration and a regular exchange of correspondence.36 In 1914, with the onset of World War I, Clemenceau played a pivotal role in persuading Monet to embark on this ambitious undertaking.3 This encouragement was particularly crucial as Monet was deeply affected by personal losses and the unfolding horrors of the war.17

Monet himself had contemplated retirement, expressing that painting had become "unremitting torture".28 Clemenceau's strong leadership and resolve during the war served as a source of inspiration for the artist.6 Viewing Monet as a vital symbol of the enduring French spirit, Clemenceau urged him to continue his artistic pursuits as a patriotic duty.28 Beyond emotional support, Clemenceau also provided practical assistance to Monet during the war, helping him secure essential resources such as gas for his cars and art supplies for his work.6

There was even a moment when a discouraged Monet considered abandoning the Water Lilies project, but Clemenceau's persistent encouragement ultimately prevailed, highlighting the strength of their bond.35 The close relationship between the artist and the statesman demonstrates how personal connections and political influence can converge to facilitate significant artistic achievements and the preservation of cultural heritage. The extensive correspondence between them offers a valuable glimpse into the evolution of the project and the depth of their mutual respect.

The Water Lilies at the Orangerie: A Symbol of Peace and National Significance

The dedication of the Water Lilies to the French nation was deeply intertwined with the aftermath of World War I, serving as a powerful symbol of peace and remembrance.4 On November 12, 1918, the day following the Armistice, Monet offered his Water Lilies to the French State as a gesture of peace.4 He viewed this act as his personal contribution to the victory, "the only way I have of taking part in the Victory," and as a tribute to the countless young Frenchmen who perished in the trenches.28 The conclusion of World War I in 1918 amplified Monet's desire to provide solace and beauty to a nation scarred by conflict.26

The Pond in June

His vision for the immersive environment of the Water Lilies was to create a sanctuary for peaceful meditation, offering respite to those whose nerves were frayed by the war's devastation.11 Initially, Monet intended to donate twelve canvases, but with Clemenceau's encouragement, this number evolved.18 The formal donation was finalized in 1922.7 The Water Lilies can be interpreted as a vibrant memorial, symbolizing resilience, beauty, and the enduring hope for peace amidst the backdrop of wartime destruction.28 Monet continued to paint these monumental works throughout the war, even as the conflict drew perilously close to his home in Giverny.6 This act underscores the profound capacity of art to respond to historical trauma, offering a powerful symbol of peace and remembrance.

Monet's Water Lilies: Inspiration, Creation, and Artistic Vision

The creation of the Water Lilies for the Orangerie was a monumental undertaking that spanned approximately three decades of Claude Monet's artistic career, from the late 1890s until his death in 1926.5 The "Grande Décoration," specifically intended for the Orangerie, became the central focus of his artistic endeavors in the final decade of his life, particularly from 1914 onwards.7

Monet’s Last Studio

The Monumental Creation of the Water Lilies

Monet dedicated himself to this project with unwavering intensity, working obsessively in a vast studio that was purpose-built at his Giverny estate to accommodate the immense scale of the canvases.3 This expansive studio, sometimes referred to as a sky-lit hall, was designed to house canvases that reached heights or widths of around two meters (six feet), allowing Monet to work on multiple panels simultaneously, a technique he often employed.3 The sheer magnitude of the project is evident in the dimensions of the final installation: the eight panels at the Orangerie collectively stretch to a length of approximately 91 meters (nearly 300 feet) 10, covering a total surface area of about 200 square meters.13

Monet in Last Studio

Even as his eyesight began to fail due to cataracts, Monet persevered with the project, demonstrating an extraordinary level of dedication to his artistic vision.4 Driven by a relentless pursuit of perfection and often plagued by self-doubt, Monet continuously reworked his canvases, even destroying some in the process.13 This period of intense focus underscores Monet's profound commitment to the water lily theme, which became a central "obsession" in his later years.3 The ambition to create such a monumental decorative scheme necessitated not only the construction of a specialized studio but also years of unwavering dedication, reflecting the artist's enduring determination to realize his artistic vision in the face of personal and physical challenges.

This painting of the bridge shows the shift in his vision due to cataracts. The colors tended to skew toward red and yellow and eventually brown.

The Orangerie: From Citrus Shelter to Artistic Sanctuary

The selection and transformation of the Orangerie museum into the permanent home for Monet's Water Lilies was a significant undertaking, reflecting a collaborative vision between the artist and his close friend, Georges Clemenceau.9 Originally constructed in 1852 under Napoleon III, the Orangerie served as a winter shelter for the citrus trees from the Tuileries Garden.8 Over time, it also functioned as a venue for various public events before being designated, after World War I, as a space for living artists to exhibit their work.9 Georges Clemenceau was instrumental in suggesting the Orangerie as the ideal location for Monet's grand Water Lilies, proposing it over the initially considered Rodin Museum.9

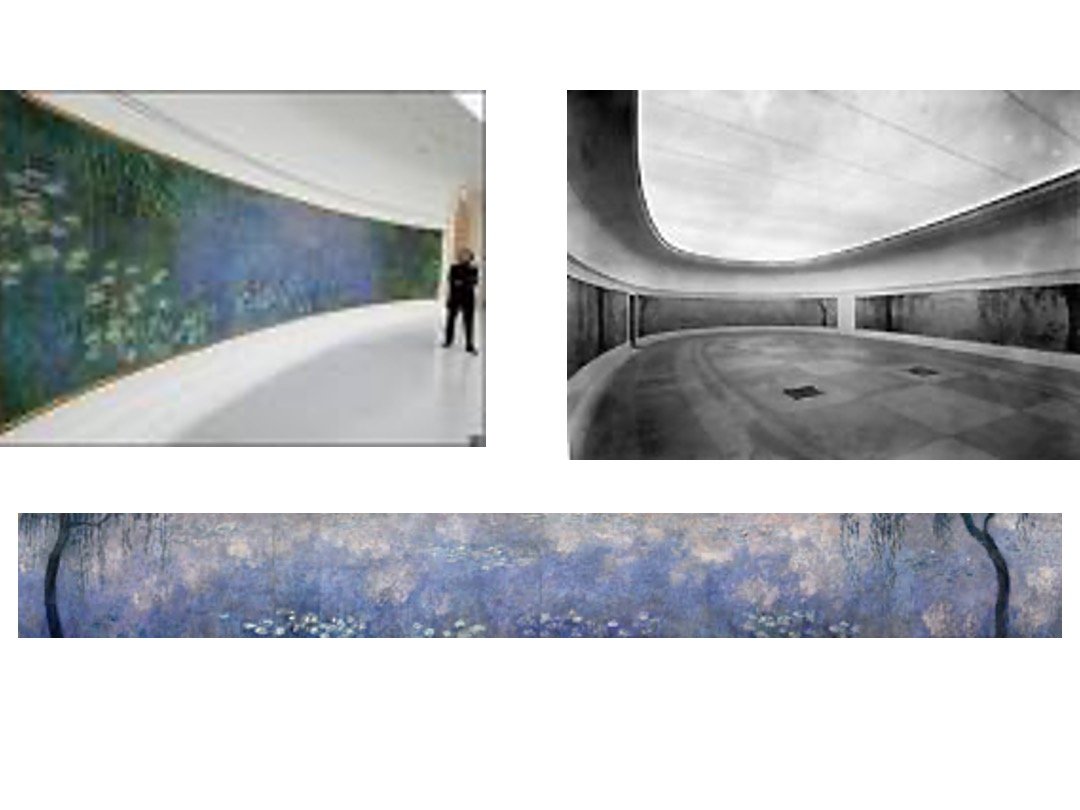

The Design and Arrangement of the Water Lilies at the Orangerie

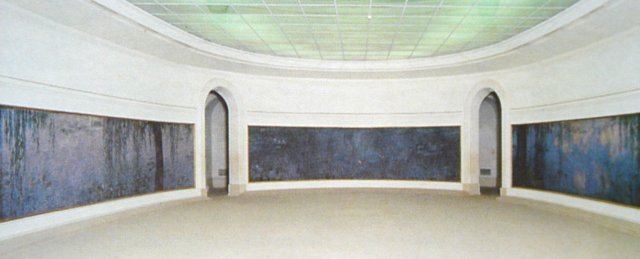

The official donation of the Water Lilies to the Orangerie was finalized in 1922.9 Monet himself took an active role in the architectural design of the two oval rooms within the Orangerie, specifically intended to showcase his monumental work.9 He collaborated closely with the architect Camille Lefèvre to ensure that the space would perfectly complement his artistic vision.9 The design of the two interconnected oval rooms was conceived to create an immersive and continuous viewing experience, symbolically representing infinity.9

Monet's intention was to evoke the "illusion of an endless whole, of a wave without horizon and without shore," drawing the viewer into a contemplative world of water and light.11 A crucial element of Monet's vision was the incorporation of natural light through skylights, which he believed would immerse visitors in a state of grace, enhancing their experience of the paintings.9 The east-west orientation of the Orangerie building was also significant, aligning with the path of the sun and the historical axis of Paris, further contributing to the intended atmosphere of the installation.9 This deliberate integration of art and architecture exemplifies the concept of proto-installation art, where the artwork and its environment are thoughtfully designed to create a unified and encompassing experience for the viewer.50

The Enduring Friendship Between Monet and Clemenceau

The culmination of the collaborative efforts between Monet and Clemenceau was the installation of the Water Lilies at the Orangerie Museum in 1927, a few months after Monet's passing in December 1926.3 The exhibit was officially opened to the public on May 16 or 17, 1927.4 Initially, the museum was inaugurated as the Musée Claude Monet, a testament to the artist's profound contribution.6 Sadly, Monet himself did not have the opportunity to witness the complete installation of his monumental Water Lilies in their intended setting before his death.11

Clemenceau at the Inauguration of the Museum.

Georges Clemenceau played a vital role in ensuring that all the necessary arrangements were finalized for the opening and dedication of his dear friend's artistic legacy.6 He even presided over the inauguration of the museum, marking the culmination of their collaborative vision.10 This event signified the realization of a long and dedicated artistic journey, brought to fruition through the unwavering support of a close friendship, even in the absence of the artist himself.

Despite the profound significance of Monet's gift to France and the unique architectural setting designed to showcase the Water Lilies, the initial public and critical response upon their installation in 1927 was surprisingly muted, lacking widespread enthusiasm.6 Some critics dismissed the monumental works as the product of an aging artist whose skills had diminished, or as mere "postcard niceties" catering to what they perceived as unsophisticated American tastes.6 One particularly harsh assessment labeled them "the greatest artistic error committed by Monet".63

This less than favorable reception can be partly attributed to the shifting artistic landscape of the 1920s, where tastes were evolving towards more modern art movements, leading to a degree of skepticism towards the Impressionist style, particularly Monet's later works.6 However, not all initial reactions were negative. Some early viewers, such as the historian Louis Gillet, recognized the unique and immersive nature of the installation, perceiving it as a unified and singular artistic experience.50 The initial lack of widespread appreciation is further underscored by the fact that when one of the panels was damaged by bombing during World War II, it remained unrepaired for two decades, indicating a certain level of neglect.11 This initial lukewarm response highlights the often-unpredictable nature of artistic reception and the way in which the value and understanding of art can evolve over time. The later recognition of the Water Lilies as a masterpiece and their significant influence on subsequent art movements demonstrate this shift in perception.

The cultural climate in France following World War I was characterized by a complex interplay of rebuilding, societal transformation, and a dynamic evolution in the artistic realm.69 The nation grappled with the immense task of reconstruction while simultaneously experiencing significant shifts in social norms and values.69 The art scene in post-war France was marked by a rich tapestry of diverse styles, ranging from figurative art and expressionism to the burgeoning movements of Surrealism and Purism.1 Paris continued to serve as a vibrant hub for artists from around the world, fostering the development of the "School of Paris," a testament to the city's enduring artistic allure.1 Artists of this period responded to the profound impact of the war in various ways, often creating works that honored the memory of absent soldiers and served as enduring memorials to the conflict.45 Within this context, Monet's Water Lilies can be viewed as a unique contribution, functioning not only as an artistic masterpiece but also as a symbol of peace and a form of remembrance in the wake of immense loss.12 However, the prevailing artistic trends in the post-war era were gradually moving away from Impressionism towards new modes of expression, which may partly explain the initial lack of widespread enthusiasm for Monet's late-Impressionistic Water Lilies.6

Despite this, Monet's later works, including the Water Lilies, contained elements that hinted at the abstraction that would later gain prominence, suggesting a forward-looking aspect to his artistic vision.7 The historical and artistic backdrop of post-war France provides crucial context for understanding the initial reception of Monet's final great project, revealing the complex interplay between artistic creation, historical circumstances, and the shifting tides of public perception.

The realization of the Water Lilies at the Orangerie was deeply rooted in the strong personal bond and shared vision between Claude Monet and Georges Clemenceau.6 Their friendship, spanning nearly three decades, is well-documented through their extensive correspondence, which reveals a relationship built on mutual respect and affection.6 They even used endearing nicknames for each other, reflecting the intimacy of their connection.35 The correspondence vividly illustrates Clemenceau's unwavering encouragement and support for Monet throughout the challenging "Grande Décoration" project, particularly during periods when Monet faced discouragement and self-doubt.6

Clemenceau's commitment to the project was so profound that he famously told Monet he would sacrifice their friendship if the artist abandoned his work on the Water Lilies.35 Their discussions also extended to the crucial matter of the installation's location, with Clemenceau playing a key role in securing the Orangerie as the permanent home for the Water Lilies and ensuring that Monet had significant input into the redesign of the space to meet his specific artistic requirements.6 The correspondence also provides insights into the difficulties and tensions that arose during the lengthy process, including Monet's repeated delays and his moments of hesitation regarding the donation agreement.37

The depth of their personal bond is further evidenced by Clemenceau's presence at Monet's deathbed.6 Following Monet's death, Clemenceau authored a book about the Water Lilies, a testament to their enduring friendship and shared artistic vision.36 The close relationship between these two prominent figures highlights the power of personal connections in shaping significant cultural and historical outcomes, with Clemenceau's steadfast support proving instrumental in the realization of Monet's monumental artistic gift to France.

The Water Lilies installations at the Musée de l'Orangerie are meticulously arranged in two interconnected oval rooms, designed to create a continuous and immersive panoramic experience for the viewer.3 Eight large-scale murals, each composed of multiple assembled panels, are housed within these two rooms.3 While all eight compositions share a uniform height of approximately 2 meters (6.6 feet), their lengths vary, collectively spanning around 91 meters (nearly 300 feet) when placed end to end.9 The arrangement of these two oval rooms is symbolic, evoking the mathematical symbol for infinity.9 Furthermore, the Orangerie's orientation, running east to west, was deliberately chosen to align with the course of the sun. The paintings are arranged so that those depicting the hues of sunrise are located in the east room, while those capturing the colors of sunset are placed in the west room, creating a visual representation of the continuum of time and space.10 The inclusion of natural light through the skylights was a critical aspect of Monet's vision for the installation, designed to immerse visitors in a luminous environment that enhances their experience of the artwork.9

Conclusion:

The collaboration between Claude Monet and Georges Clemenceau to create the grand decorations of Water Lilies for the Orangerie stands as a remarkable testament to the power of friendship, artistic vision, and national sentiment. The idea, germinating from Monet's profound connection with his Giverny water garden in the late 1890s, evolved into a monumental project under the steadfast encouragement of Clemenceau, particularly during the tumultuous years of World War I. Monet's dedication to capturing the ephemeral beauty of his water lilies spanned decades, culminating in the donation of these expansive murals to France as a symbol of peace following the Armistice of 1918. The Orangerie, carefully adapted to house these masterpieces, became a sanctuary for art, embodying Monet's vision of an immersive and contemplative space. While the initial public and critical reception in 1927 was somewhat reserved, the Water Lilies have since gained universal acclaim, recognized as a pivotal achievement in modern art. The enduring bond between the artist and the statesman, evidenced by their extensive correspondence, underscores the profound human element that underpinned this significant cultural endeavor. The layout of the eight panels in the two oval rooms of the Orangerie, designed to evoke infinity and bathed in natural light, offers viewers an unparalleled opportunity to experience Monet's artistic vision in its full, immersive glory. The Water Lilies at the Orangerie remain a powerful symbol of resilience, beauty, and the enduring legacy of Claude Monet, forever intertwined with the historical context of post-World War I France and the remarkable friendship that brought them into being.

1. 20th-century French art - Wikipedia, accessed April 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/20th-century_French_art

2. French Art History in a Nutshell - Artsy, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-french-art-history-in-a-nutshell

3. Water Lilies | painting series by Claude Monet | Britannica, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Water-Lilies-Monet-series

4. Water Lilies (Monet series) - Wikipedia, accessed April 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_Lilies_(Monet_series)

5. Claude Monet Paintings, Bio, Ideas - The Art Story, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.theartstory.org/artist/monet-claude/

6. Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet & the Paintings of the Water Lilies - Kim Minichiello, accessed April 12,2025,https://www.kimminichiello.com/kim-minichiello/2018/4/13/mad-enchantment-claude-monet-the-paintings-of-the-water-lilies

7. Monet's Water Lilies Are Shown at the Musée de L'Orangerie | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/monets-water-lilies-are-shown-musee-de-lorangerie

8. History of the Orangerie museum - Come to Paris, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.cometoparis.com/paris-guide/paris-monuments/musee-de-l-orange rie-s961

9. Musée de l'Orangerie - Wikipedia, accessed April 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mus%C3%A9e_de_l%27Orangerie

10. From the orangerie to the museum | Musée de l'Orangerie, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/node/11. A Visit to Le Musée de l'Orangerie, The Cycle of the Water Lilies (Nymphéas) by Claude Monet with TSLL – The Simply Luxurious Life®, accessed April 12, 2025, https://thesimplyluxuriouslife.com/monetlorangeriewaterlilies2022/

12. Monet's Water Lilies, 2nd Grade | The heART of life, accessed April 12, 2025, https://thecolorsofanartroom.wordpress.com/2015/03/08/monets-water-lilies-2n d-grade/

13. History of the Water Lilies cycle | Musée de l'Orangerie, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.musee-orangerie.fr/en/node/33

14. Claude Monet | Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437127

15. Painting Monet's Water Lilies - Erin Hanson's Blog, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.erinhanson.com/blog?p=painting-monets-water-lilies

16. Looking at the Masters: Claude Monet - The Talbot Spy, accessed April 12, 2025, https://talbotspy.org/looking-at-the-masters-claude-monet/

17. Claude Monet's Water Lily Paintings - Art-Info - Reproduction Gallery, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.reproduction-gallery.com/blog/claude-monets-water-lily-paintings/

18. 10 Facts You Might Not Know About Claude Monet's 'Water Lilies', accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.claude-monet.com/waterlilies.jsp

19. Claude Monet: the Visionary, the Painter, and the Gardener - Discover + Share, accessed April 12, 2025,https://discoverandshare.org/2020/09/15/claude-monet-the-visionary-the-painte r-and-the-gardener/

20. Monet - Insights - Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, accessed April 12, 2025, https://insights.famsf.org/late-monet/

21. The Real Story and Facts Behind Claude Monet's Water Lilies - The Tour Guy, accessed April 12, 2025,https://thetourguy.com/travel-blog/art-history/facts-about-claude-monet-water- lilies/

22. Paris, France: Monet's Dreamy Water Lilies - Rick Steves' Europe Travel Guide - YouTube, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QD9WeM6SW00

23. Monet's Luminous 'Water Lilies' Transport Viewers to His Giverny Garden - Sotheby's, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/monets-luminous-water-lilies-transports-v iewers-to-his-giverny-garden

24. Claude Monet | Water-Lilies | NG6343 | National Gallery, London, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-water-lilies

25. Orangerie Museum in Paris - - Exploring Our World -, accessed April 12, 2025, https://exploringrworld.com/orangerie-museum-paris/

26. Monet's Water Lilies, Musée de l'Orangerie | get back, lauretta!, accessed April 12, 2025,https://getbacklauretta.com/2019/07/18/monets-water-lilies-musee-de-lorangerie/

27. Monet at the Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris - France Just For You, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.france-justforyou.com/blog/monet-at-the-musee-de-lorangerie-par is

28. Claude Monet's Water Lilies: Famous Art Explained | Rest In Pieces, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.restinpieces.co.uk/blogs/news/claude-monet-water-lilies-famous-ar t-explained

29. Claude Monet. Water Lilies. 1914-26 - MoMA, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80220

30. Monet's Water Lilies | Definitive Guide - Odyssey Traveller, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.odysseytraveller.com/articles/monets-water-lillies/

31. Nympheas, 1905 by Claude Monet, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.claude-monet.com/nympheas.jsp

32. Water Lilies | The Art Institute of Chicago, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/16568/water-lilies

33. Later in Life, Claude Monet Obsessed Over Water Lilies. His Paintings of Them Were Some of His Greatest Masterpieces - Smithsonian Magazine, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/claude-monet-became-obsessed-water-lilies-paintings-were-some-greatest-masterpieces-180984898/

34. Explore fascinating facts and the craze behind Monet's water lilies - teravarna, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.teravarna.com/post/8-things-about-monet-s-water-lilies

35. Claude Monet & Georges Clemenceau | Normandy Melody, accessed April 12, 2025,https://www.normandy-melody.com/blog/claude-monet-georges-clemenceau/

36. Georges Clemenceau and Claude Monet, accessed April 12, 2025, https://www.maison-de-clemenceau.fr/en/discover/the-many-facets-of-georges- clemenceau/georges-clemenceau-and-claude-monet

37. The Unlikely Friendship Between a Painter and a Politician - France Today, accessed April 12, 2025,https://francetoday.com/culture/the-unlikely-friendship-between-a-painter-and-